Hope Happens Here: Jerod Nieder

In 2011, when Jerod Nieder was 28 years old, he traveled to Mexico with his family.

As soon as they checked into the resort, Jerod ran down to the beach with his siblings, dove into the sandbar and broke his neck.

"That moment changed the trajectory of my life," says Jerod. "I felt like my parents gave me a perfectly good body, and I messed it up."

An air ambulance transported Jerod to Craig Hospital in Denver. Despite four months of rehabilitation at one of the best centers in the country, his hips were deteriorating so rapidly, doctors recommended that he get care at an academic medical center. It turns out, Jerod's injury exacerbated a congenital hip condition that had gone undetected his whole life. His hips were out of the socket, and the tissue was dying.

Jerod traveled to Mayo in Rochester searching for solutions; that's where he learned about a groundbreaking new research effort called. "I wandered into a neuroscience symposium with my mom and heard the principal investigator of the study, Susan Harkema, speaking," Jerod says. "She was clear that epidural stimulation wasn't a cure, but that it can make things better for people with spinal cord injury."

Jerod waited one hour to speak to Dr. Harkema after the presentation. When they finished talking, he set his sights on a new goal: Joining The Big Idea study at the University of Louisville. The Big Idea has an infrastructure of more than 150 health care professionals who support people with spinal cord injuries (SCI), but precious few slots for participants. Researchers use a lottery system to select individuals with SCI from a national database. All Jerod had to do was register for the database and wait for his number to be called.

As he approached the one year anniversary of his injury, Jerod underwent surgery to repair one hip and a week later, he had a second surgery to repair the second. When his hips continued causing problems, he underwent another repair in 2013. "That's when I was finally able to start recovering," says Jerod, who trained at a rehabilitation center near his home in Kansas, trying to restore remaining function. Then four years after Jerod registered for The Big Idea, doctors invited him to be part of the study.

As he approached the one year anniversary of his injury, Jerod underwent surgery to repair one hip and a week later, he had a second surgery to repair the second. When his hips continued causing problems, he underwent another repair in 2013. "That's when I was finally able to start recovering," says Jerod, who trained at a rehabilitation center near his home in Kansas, trying to restore remaining function. Then four years after Jerod registered for The Big Idea, doctors invited him to be part of the study.

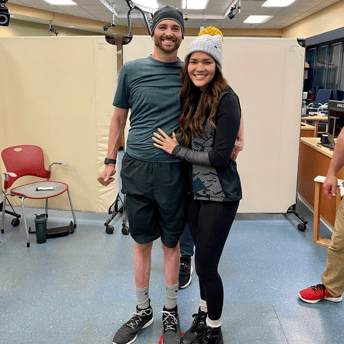

Jerod completed intake evaluations in August 2015 and moved to Louisville, eight hours away from his family, in October. As it happens, Jerod fell hard for his caregiver, Hanna, and the pair have been a power couple ever since. But his journey to receiving an epidural stimulator wasn't without hiccups. During his first qualifying evaluations, the surgeon identified an abnormality in his spine. He was not a candidate.

Still, Dr. Harkema had hope for Jerod. "She came to me and said, 'Your opportunities in Louisville are not over,'" says Jerod. "She tried to pick me up and encourage me to stay the course."

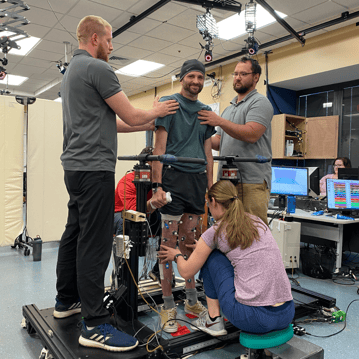

Six months later, in fall 2018, Jerod's spine had stabilized, and doctors felt comfortable forging ahead with implanting an epidural stimulator. Before surgery, Jerod underwent extensive pathway studies so doctors could determine the ideal placement for the stimulator, a thin plastic implant that contains more than a dozen electrodes. Doctors place the device and fire up the electrodes from top to bottom, hoping the muscle sensors will pick up electrical activity in specific muscles. "I felt like I was part of the space program," Jerod says.

After two weeks of bed rest, Jerod went to the rehabilitation center, and doctors turned on the stimulator. "Hanna was sitting next to me, and I just started moving my leg," Jerod says. "The tears started flowing, and we were FaceTiming with family members, completely astonished at what we were seeing. That one moment doesn’t change everything, but it opens the door to possibility."

After two weeks of bed rest, Jerod went to the rehabilitation center, and doctors turned on the stimulator. "Hanna was sitting next to me, and I just started moving my leg," Jerod says. "The tears started flowing, and we were FaceTiming with family members, completely astonished at what we were seeing. That one moment doesn’t change everything, but it opens the door to possibility."

Immediately after his injury, Jerod had very little arm movement. After a few months, he could drive a wheelchair and feed himself, but not well. Now, with the help of the stimulator, Jerod's strength has increased exponentially. He has stimulator settings for leg raises, sit-ups, sitting posture, standing and stepping (treadmill training). But according to Jerod, the stimulator's greatest impact is on basic functions, such as blood pressure control and sleep.

Where once Jerod would flop all over the bed, preventing both him and Hanna from a restful night of sleep, now he's able to sleep soundly. "I have so much more energy," Jerod says, adding that he and Hanna can go to dinner with friends, and he can remain upright and engaged for the entire meal; something that was impossible for him before the stimulator.

But Hanna emphasizes that Jerod's achievements are a direct reflection of the amount of effort Jerod puts into the program. From 8 a.m. until the trainers kick him out at 5 p.m., Jerod pushes himself with occupational therapy, physical therapy, research involvements, and clinical appointments.

"He's like Iron Man," Hanna says. "He doesn't tire out. He participates in every available study, and he's the hardest worker the staff has ever seen."

Jerod is quick to point out that none of it would be possible without Hanna. He has to report to the program every day and complete tasks at home. For portions of the program, he's required to take his blood pressure every 10 minutes for six hours straight. "That doesn't happen without reliable caregiving," he says.

But Hanna is not only his full-time caregiver, but she's also the reason he's enjoying life again. "When I met Jerod, he never left his apartment outside of training," Hanna says. Now, he and Hanna go to brunch every Saturday (it was one of her prerequisites in exchange for being his full-time caregiver). They participate in accessible activities from bike riding to adaptive rowing, and they love to travel. They saw Hamilton in Chicago, ice skated together at Rockefeller Center, and next year, they're planning to go scuba diving in Hawaii. But first, on the 10-year anniversary of Jerod's injury, they'll be getting married!

But Hanna is not only his full-time caregiver, but she's also the reason he's enjoying life again. "When I met Jerod, he never left his apartment outside of training," Hanna says. Now, he and Hanna go to brunch every Saturday (it was one of her prerequisites in exchange for being his full-time caregiver). They participate in accessible activities from bike riding to adaptive rowing, and they love to travel. They saw Hamilton in Chicago, ice skated together at Rockefeller Center, and next year, they're planning to go scuba diving in Hawaii. But first, on the 10-year anniversary of Jerod's injury, they'll be getting married!

"I'm half Korean, and Jerod suggested we do the traditional Korean wedding ceremony," Hanna says. "A key part of the ceremony includes moving from a standing position with your hands on your forehead to kneeling all the way down until your forehead touches the floor — and Jerod is committed to making it happen with the help of his stimulator." What greater testament to the couple's commitment not only to each other, but also to making the impossible possible.

Join Our Movement

What started as an idea has become a national movement. With your support, we can influence policy and inspire lasting change.

Become an Advocate